Fire blight - Erwinia amylovora

Erwinia amylovora is the most aggressive pathogen in fleshy fruit species, especially in pear and apple, as well as in other species of the Rosaceae family. The diseases caused by this bacterium are known as Fire Blight. Many other species can be infected by this bacterium, including cultivated or wild ornamental species.

-

Symptoms

The first signs of E. amylovora are manifested in flowers and small branches, being able to spread to large and the trunk causing the death of the tree.

In infected flowers, wet rot is distinguished, and then begin to shrivel until they dry completely falling to the ground or remaining attached to the tree. As the disease spreads, leaves and small nearby branches begin to show similar symptoms.

In the case of outbreaks and small branches, the disease progresses to the branches where canker sores or obvious ulcers appear.

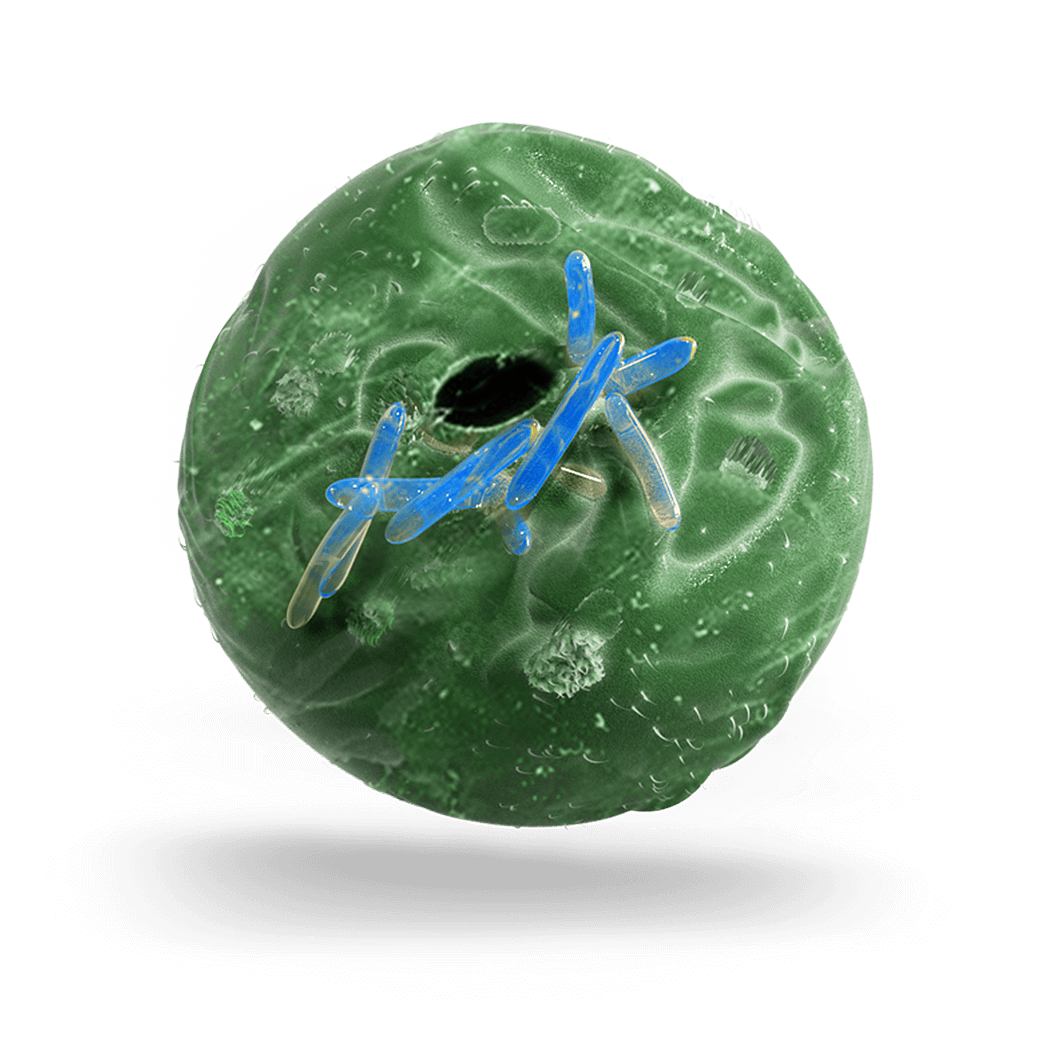

Infected immature fruits end up dying, but may remain attached to the branches several months after the onset of the infection, serving as a reservoir for the bacteria.

-

Development of the disease

Erwinia amylovora survives during adverse conditions development in the margins of the lesions that it causes to branches and, probably, in new shoots and healthy tissues. In spring, the bacteria are activated and spread to the bark or healthy nearby organs.

Bacterial exudates appear when the inflorescences begin to open. At this time, insects such as bees, flies and ants are attracted by the exudates becoming vectors of the bacteria, spreading the disease to other flowers in which they feed.

These bacteria can also be dispersed by rain or air when the exudates dry completely and remain on the surface of infected tissues.

In the leaves the cycle is very similar, where E. amylovora penetrates through wounds, stomata or hydathodes. From the leaves, the bacteria transfer to the branches through the petioles.

Pseudomonas syringae

The spots and burns on leaves, stems and fruits caused by bacteria are associated with the genera Pseudomonas and Xanthomonas. Of all the species that make up these genera, Pseudomonas syringae is one of the bacteria with the greatest economic impact on agriculture.

Its importance is due to its wide worldwide distribution and the great diversity of cultivated species that can infect. The isolates of this species are assigned to around 50 described pathovaries, whose only difference is in the specific host they attack since they are morphologically identical.

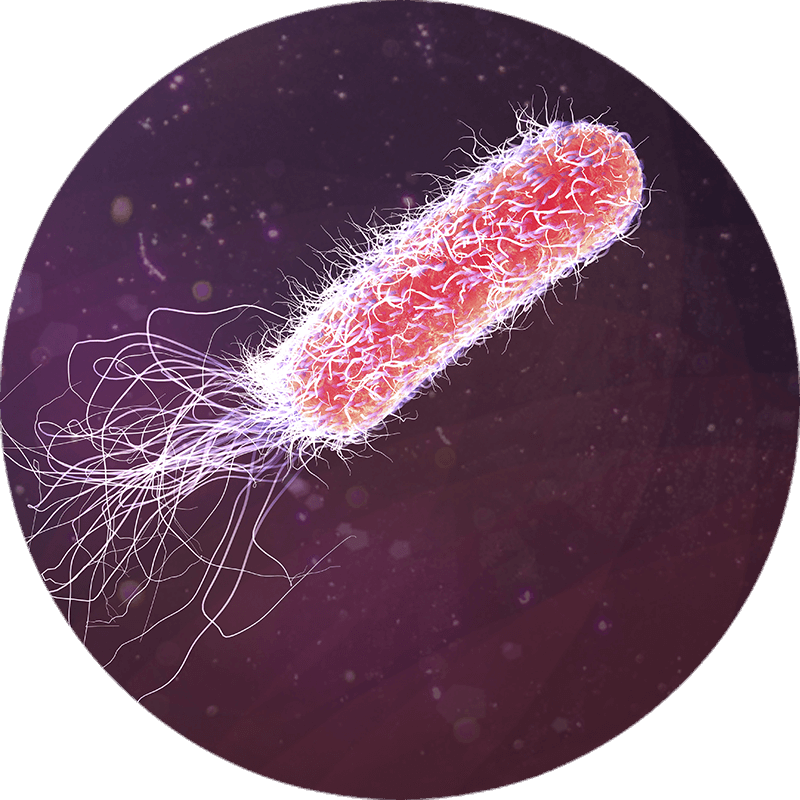

At the microscopic level, P. syringae morphologically appears as a straight cane or something curved and mobile, with polar flagella that allow it to move. It is a common inhabitant of the floors.

-

Symptoms

The symptoms associated with P. syringae may vary depending on the different individuals or pathovars.

The most common symptom is the appearance of spots, usually of different sizes, on leaves, stems and fruit.

These spots end up appearing as circular necrotic areas.

Depending on the pathovar, the lesions may be of different sizes. For example, Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato causes smaller lesions than other plant pathogenic Pseudomonas bacteria. Another characteristic symptom that may appear is a moist halo surrounding the spots, separating healthy tissues from the lesion. With the progression of the disease, the lesion becomes a necrotic area.

-

Development of the disease

Pseudomonas syringae is a bacterium that inhabits and remains in the soil on plant debris and decaying organic material. However, the level of their populations drops in the absence of a susceptible host.

The dispersion of the bacteria is mainly done through raindrops and transmission by insects during their feeding. Other routes of transmission may be plant debris or contaminated work tools and machinery.

The entry of P. syringae into the plant occurs through stomata, hydatodes and wounds. Once inside, the bacteria multiply intercellularly at a very high growth-rate and secrete large amounts of enzymes. The result of this growth of the bacteria inside, results in the appearance of the diseases typical spots, which consist of dead cells surrounded by healthy cells where the infection has not reached. If the bacteria continue to grow, the collapse and death of parenchymal cells occurs. Lesions caused by P. syringae are often entry points for other pathogens, mainly of bacteria and saprophytic fungi.

Xanthomonas campestris

Xanthomonas campestris is a gram-negative bacterium that causes a wide variety of phytopathologies. It attacks different hosts, over 20 pathovars have been identified for their distinctive pathogenicity in a wide range of plants, including crops and wild plants.

The diseases generally affect the stems, leaves and fruits causing significant losses when the conditions are suitable for the pathogen.

-

Infective cycle

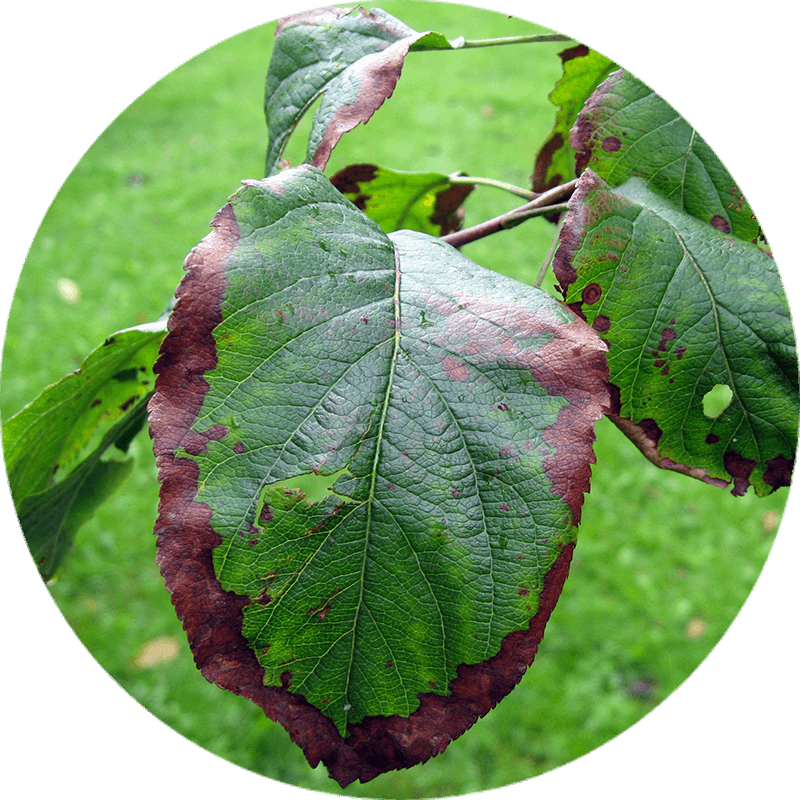

The primary source of inoculum is the infected seed. During germination, seedlings become infected through the epicotyl and cotyledons developing blackened margins and shrivel. The bacterium progresses through the vascular system to the young leaves and stems, where the disease manifests itself as chlorotic to V-shaped necrotic lesions, extending along the margins of the leaf. Under humid conditions, the bacteria can spread through wind, rain, water splashes and mechanical equipment to neighboring plants.

The natural invasion route of the Xanthomonas campestris is through the hydathodes, although the wounds caused by insects on the leaves and roots of the plants can also serve as a place of entry. Occasionally, infections also occur through stomata. Hydathodes provide the pathogen with a direct route from the margins of the leaf to the plant’s vascular system, causing a systemic infection in the host. The invasion of the veins leads to the production of the infected seed.

Bacteria present in plant debris can serve as a source of secondary inoculum.

-

Symptoms

X. campestris causes great losses in agriculture due to its habitat in plants. It can live in the soil for a year and spread through irrigation water. X. campestris can be identified by black lesions that appear on the surface of infected plants. The pathogen interacts first with the host by secreting a series of effector proteins, which can behave in an avirulent way disguising themselves to secrete several hypersensitive reactions and external proteins in order to produce interaction with host cells. Then, X. campestris is directed to vascular tissue, causing darkening and marginal chlorosis. The bacteria seep into the leaf into stomata, hydathodes and into epidermal cells starting a new lesion. In seedlings serious infections occur. Since the disease progresses throughout the entire plant, the main stem cannot form, there is a delay in growth and darkening of the veins. Finally, the bacteria proliferate through the vascular system, causing the seeds to become infectious and new infections occur.

.png)

.png)